Modular Architecture is a set of principles and methodologies used in Sitecore Habitat to showcase Sitecores recommended best practices for solution architecture in a Sitecore solution. This is my second post on Modular Architecture and Sitecore Habitat. If you haven’t read the first post already you can read it here.

What are layers in Modular Architecture?

The concept of layers is a concept in Modular Architecture originally described in Pentia Component Architecture.

The concept has been introduced to support a number of principles of component design described by Uncle Bob.

Note that the layers in Modular Architecture are not equivalent to the layers seen in 3/n-tiers architecture even though they bear resemblance in terms of dependency direction.

When following a regular component based design as described by Uncle Bob there are no fixed layers. The dependency flow between components are not formalized but has to conform to the principles of component design.

Not all developers know these principles by heart and even the ones who do tend to be forgetful sometimes.

The layer concept support us developers by making the dependency flow completely clear everywhere in the solution, in Sitecore, in Visual Studio and even in the file system.

Furthermore the layers provide a structure that is extremely suitable for creating and maintaining website solutions of any size.

The layer concept is introduced specifically for this type of solutions and will not fit into all software design in general. But for Sitecore and most other web based solutions the layer concept is absolutely brilliant and support both new and experienced developers in producing maintenance friendly clean code.

A layer is physically described in your solution by folders in the filesystem, Visual Studio and Sitecore along with namespaces in code.

A layer defines in which direction modules can depend on other modules.

It is all about dependencies so let us start with remembering the Stable Dependencies Principle or SDP which is one of the corner stone principles in Modular Architecture

The dependencies between packages should be in the direction of the stability of the packages. A package should only depend upon packages that are more stable than it is.

http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/stability.pdf

This principle tells us that a module should only depend on a module which is more stable than itself.

What is stability then?

If I called a person unstable it would rarely be meant as flatter. But this is not the case with modules, unstable modules are not meant as an insult to the module, the developer or any one else.

Unstable code is just something that we have to realize is a part of all software solutions.

Some code more likely to change than other code. Some code changes very often, some code get changed regularly whilst other code rarely changes.

This is the world we live in with customers, requirements, designers, new technology and so on. This is not the same as stability, we can call this fragility or mutability. Stability in our term is a measurement for number of in- and outgoing dependencies .

The obvious thing to do is to ensure that nothing ever depends on code that you know will change often.

This is a somewhat idealistic and ambitious statement since we actually live in the real world. But let’s stick to this statement for now and discuss it again later when we have introduced the layers.

To sum up stability:

- Code fragility is a way of expressing how likely it is that a the code in a module and it’s interfaces will change. Stability is a way of expressing how many in- and outgoing dependencies a piece code has. Many dependencies and it is unstable, few dependencies it is per definition stable.

- Stability is important since if you depend on a module that changes often then these changes will scaffold to all the depending modules as well.

- If dependencies are not controlled then you will end up with spaghetti where one change one place will cause changes in another seemingly unrelated part of the solution.

- Too much spaghetti, will create an unstable code-base , and make your solution hard or impossible to maintain over time. Both costs and headaches will grow and grow until someone pulls the plug and kills the solution.

Stability is not about how often the code fails and throw up on you, as the word stability otherwise could imply. One might implicitly conclude that code which fails often is (hopefully) very likely to change since it will be updated to fix the bugs thus should be considered unstable. But lets pretend that all code just works as it is supposed to.

Abstractions

Now we know what stability is and we have the Stable Dependencies Principle that tells us how our dependencies in the solution has to be.

This brings us to another corner-stone principle in the Modular Architecture layer concept, the The Stable Abstractions Principle or SAP .

Packages that are maximally stable should be maximally abstract. Unstable packages should be concrete. The abstraction of a package should be in proportion to its stability.

http://www.objectmentor.com/resources/articles/stability.pdf

In conjunction with the Stable Dependencies Principle we can conclude that a module which other modules depend on should be more abstract than the depending module.

This mean that the foundation modules in your solution should be conceptually abstract whilst the closer you get to actual pages shown on the website the more concrete the modules containing the code has to be.

What does it mean that a module is abstract?

Remember we are talking about modules and not classes. A common misunderstanding of this principle is that all the classes in the module always has to be completely “abstract” so they “protect” the dependent modules. This is not the complete case, it is the interfaces of the module that should be more abstract than the dependent code, the underlying implementation within the module does not have to be abstract itself.

What is meant with abstract in this case is that the modules has to be on a conceptually higher level in the solution domain.

Presentation is concrete, this means renderings are concrete. Design is very concrete, specific pagetypes on a website are very concrete.

Is everything else in a Sitecore solution to be considered abstract then? No, but this is a good rule of thumb for determining what is definitely not to be abstract.

For a module to be abstract it means being abstract towards its consumers, or to turn it, the consuming modules, or dependents, should be more concrete that then the module they consume, depend on.

A module that cover solution specific functionality on a high level that several other modules depend on has to be more abstract than the modules that depend on it.

If a feature that depend on this specific functionality change, the module that contain the functionality will not change and neither will the other features that depends on the same functionality. When this is the case then the module that the specific functionality is on a higher level than the modules that depend on it thus should be more abstract.

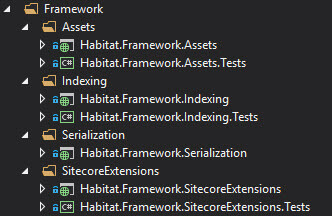

Lets look at an example of an abstract module from Sitecore Habitat

The Habitat.Framework.Indexing module is really an implementation of Sitecore Content Search but it is not named ContentSearch after the technology but Indexing due to its responsibility. Who knows Sitecore might change the name and the API in the future but the responsibility that the module has is still required in the solution.

As an example, I once worked on a solution that had OMS implemented with Sitecore 6.3. This solution had a module called OMS. Then the name changed to DMS and now Sitecore calls is xDB / Experience Platform. The name and API has changed but the responsibility of the module has not and since other modules are dependent on it all of these should not have to change if the responsibility of the module does not change.

You will encounter two general types of abstract modules in a Sitecore solution.

Technology specific

These modules are directly tied to a specific technology or API that is a core foundation in the solution. Sometimes these modules can mature into being completely solution independent and then extracted and precompiled into an API. A good example on this is the SitecoreExtensions module in Sitecore Habitat.

Solution specific

Solution specific modules has a specific responsibility in this specific solution domain that is fundamental for the rest of the solution.

Sometimes it will be a combination of the two types. As an example, a module that imports AD users, such a module could both contain solution specific models along with technology functionality. The name of such a module could be ActiveDirectory or Employees as examples depending on the module’s responsibility in the solution.

Abstractions has to stop somewhere. If your customer bought a Sitecore solution, do not try to abstract Sitecore away so it can be replaced later on. Abstractions based on responsibility will ease maintenance but abstracting code just for the sake of abstraction is just a waste of time and will cause loads of technical debt.

Now we know a bit about abstractions and how to keep dependencies between modules based on their responsibility in our solution.

But what is a module at all and how do we decide what belongs in a module.

Common closure

This brings us to the Common Closure principle which tells us what should be in a module

The classes in a component should be closed together against the same kinds of changes. A change that affects a component affects all the classes in that component and no other components.

Agile Principles, Patterns and Practices, Robert C. Martin, chapter 28 – Packages and components

I like to simply re-phrase this principle into

What changes together, should live together, alone.

Anders Laub

The word alone comes from the phrase “A change that affects a component affects allthe classes in that component”. This means that we cannot just make big modules with various things in them and still follow the principle, this will break it.

In Sitecore Modular Architecture it is not only classes that changes together that should live together. It is everything that will change with that module that should live together. Beside code this mean items, templates, renderings, configuration and so on.

We now have a principle that tells us how to decide what belongs in a module.

Remember it is not about specific presentations or design, it is about domain responsibility.

Domain responsibility often simply means that it is code that uses the same data structure and share some logic. Since when this changes due to some requirement or technology change then the module will change.

Following the Common Closure principle also mean that some modules will be very small and some will be very big. A module can almost be of any size depending on it’s responsibility.

It also tells us never to have general “Toolbox” or “Utilities” garbage bin modules with mixed responsibility.

Why is the Common Closure Principle so important in terms of dependencies?

Common Reuse

The Common Reuse Principle tells us why.

The classes in a component is reused together. If you reuse one of the classes in a component, you reuse them all

Agile Principles, Patterns and Practices, Robert C. Martin, chapter 28 – Packages and components

This principle states a fact that you always have to be aware of.

When you depend on one class in a module you depend on all the classes in that module, not just the one you are using.

In a Sitecore solution this also mean when you depend on a base template then you depend on the whole module to which this base template belongs.

The reason for this is that you do not know the inner-workings of the module that you depend on. You do not know what a change in this module in the future might mean for the class that you depend on.

So only the stuff that changes together should live together and everything that changes together should live together.

More theory?

There are other principles that are important to look at as well but the ones presented here will be sufficient to understand the reasoning behind the layer concept.

I highly encourage you to read chapter 28 in Agile Principles, Patterns and Practices by Robert C. Martin aka Uncle Bob, if you are interested in learning more.

The Basic Layers in Modular Architecture

Now we have the basic theoretical knowledge in place that is required to understand the layer concept in Modular Architecture.

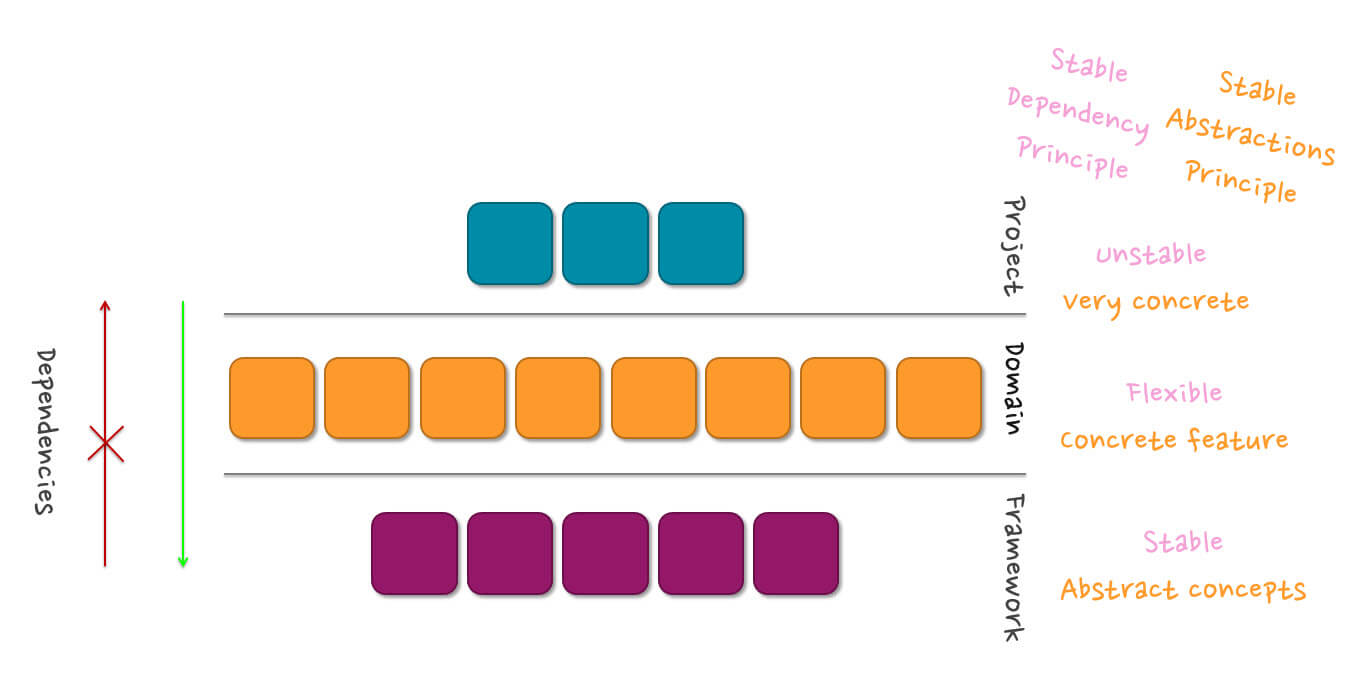

We have three basic layers in the architecture, the names can vary but their purpose cannot.

I will mention another name that might help you understand the layer responsibility better. Naming is secondary to understanding the principles behind.

Project Layer

This layer provide the context of the solution. This means actual pagetypes, layout and design. It is on this layer where all the features of the solution is tailored together.

Each time there is a change in a feature, a new one is added or one is removed, then this layer will change. The layer also contains the concrete design of the solution. This means that in terms of the Stable Dependencies Principle then the modules on this layer are unstable. The most unstable modules in your solution.

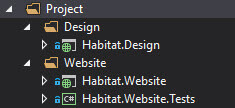

The project layer should be small and contain few modules. Typically in a single website solution this will only be two modules, Design and Website / PageTypes. These contain little or no pre-compiled code but instead consist of markup, styling, layout and templates of the item types in Sitecore which the editors can create.

There is not strict layering within the project layer. In the case of Design and Website then the Website module will have a weak dependency on the Design module since the pagetypes will be dependent on the styling provided by Design.

Another name for this layer could be Context

Domain Layer

The domain layer contain concrete features of the solution as understood by the editors and owners of the solution. The features are expressed as seen in the domain of the solution and not by technology. This means that the responsibility of a Domain layer module is defined by the intent of the module as seen by an end-user and not by the underlying technology. The module responsibility and name should never be decided by specific technology. It should always be decided by the module’s responsibility.

Border-cases will occur sometimes, as an example a module that implements simple Google Site Search might be named GoogleSiteSearch since this can be understood by the editors and the module is tightly coupled to Google Site Search. Nothing will be re-usable or directly exchangeable if another search engine should replace Site Search. If another module has to search and the apparent solution is to search using Google Site Search then a new module should be extracted into a more abstract module, most likely simply called Search where the GoogleSiteSearch is kept for the presentation and the abstract module that gets the search results can be used by other modules. This module would then be placed on the Framework layer to support SDP and SAP.

MetaData is another example where the name borders with the underlying technology instead of the responsibility. But html meta tags on a page is really meta data so the name still conforms with the rules for this layer.

Each Domain layer module has to strictly conform with the Common Closure principle. What changes together should live together alone. This ensures that changes in one feature does not cause changes anywhere else. Features can be added modified and removed without impacting other features.

Strict layering within the Domain layer is very important. One Domain module must NEVER depend on another Domain module. Breaking this will make you lose many of the benefits that Modular Architecture provides.

Another name for this layer could be Features

Framework Layer

This layer contain modules that is the foundation of your solution. When a change occur in one of these modules it will impact other modules in the solution. This mean that these modules are the most stable in your solution in term of the Stable Dependencies Principle.

The modules are conceptually abstract and does not contain presentation in the form of renderings since this are to be considered concrete. Some framework modules might still contain markup in code though. Examples on this is precompiled webcontrols and html helper functions, these should never contain direct hardcoded references to styling in the form of class names or id’s. If such domain or project specific knowledge is needed then this is passed as parameters from the depending module.

There is not Strict Layering on the framework layer. This means that one framework module can depend on another framework module in the solution.

Another name for this layer could be Foundation.

The dependency direction between the layers are strictly one way conforming with the Stable Dependency Principle. The below illustration shows each layer and its relation to SDP and SAP.

So the layers basically support the principles that then ensures a low coupling in your solution.

Lets look at what type of modules that can exist on each layer using Sitecore Habitat as an example.

Notice that the modules in Sitecore Habitat is not only the module code itself in Visual Studio. Modules can also contain test projects which are only related to the specific module. This illustrates how Sitecore Modular Architecture supports and even encourage test-ability in your solution. Also the serialized items from Sitecore is located in the same structure making each Module self-contained.

Project / Context

The Project layer contain the aforementioned two projects Website and Design. The Design project contain styling and scripts to realize a specific concrete design.

The Website project contain only views that define the layout of pages on the website along with the overall configuration and some code to transform the configuration.

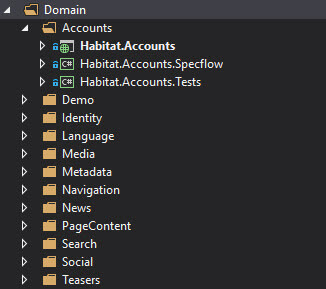

Domain / Features

The Domain layer consist of all the actual features found on the website.

The naming of each module clearly shows its responsibility in the solution domain and not the underlying technical implementation.

Framework / Foundation

The Framework layer consist of modules that is the foundation of the solution. Remember the two types of abstract modules that I presented before? The framework layer modules found in Sitecore Habitat are all technology specific but the naming is not based on the underlying technology but instead their responsibility.

The three layers are all that is needed in most solutions and are also the templates for all layers that can be introduced in larger setups.

In a coming post I will discuss advanced layering techniques in Modular Architecture where these basic layers are used to support large complex solutions that contain multiple subsites and brands in different ways. Basically keep in mind that these three layers are the basis for the concept of layers, not all there is to it.

Coming back to stability

Is only rock-solid completely 100 % in-fragile code allowed on your framework/foundation layer?

Sometimes requirements force you to rely your solution on something volatile that you do not control yourself.

So the answer is clearly no, everything on the framework layer cannot be rock-solid completely protected from change.

It is an ambition but reality will often kick in and you have a requirement that breaks our idealistic ambitions.

A solution is also never more stable than what it’s foundation depends on. Dependencies are inherited. In our case with Sitecore solutions this mean that our solutions will never be more stable than Sitecore. Sitecore will never be more stable than .NET and the various third-party libraries that Sitecore also depends on.

If a framework module that is business critical due to some requirements has to rely on a third-party product that is fragile then this framework module will be as fragile as the third-party product and all modules that rely on this framework module will be just as fragile.

There are two module design choices that can be used to come around this:

Interface the third party API away

A common approach, hide the changes away through clear interfaces that you define for your solution. A real good approach if the interfaces are simple and the parts you need in your solution are not likely to change.

Predicting the future is hard and things seldom turns out as you anticipated. The same applies for software so this approach is not always the best way to follow. The third party code and requirements to it might change very frequently. The supplier of the API might also know nothing about good software architecture and dependencies and through the Common Reuse principle cause havoc in your solution.

The suppliers might also be working after the approach try fast, fail fast so changes are to be expected all the time, new features evolve quickly and change. Changes in the API that you do not control will then cause changes to your interfaces thus cause changes in all depending modules and that typically degrades the quality of all modules and builds up a lot of technical debt.

IoC using DI containers can be good in assisting you with abstracting a third-party API away but if not done correctly or if not suitable for the situation it can also be disastrous.

Dispensable Design of Domain Feature Modules

Keep both the module itself and the modules that depend on it easily dispensable.

That means simple small modules, uncomplicated pragmatic but effective code, no abstractions. Ensure that it is quick to re-write all parts of the module, so it will be fast to replace code if it starts to become too dirty. Remember no other feature modules rely on the modules on the Domain layer, so replacing a Domain layer module will only have impact on the Project layer which is unstable anyway so these changes are expected. Simplicity is absolute key in each dispensable module. The approach supports the Try fast, fail fast paradigm.

My preferred choice vary depending on the third-party module, its usage and so on. There are many factors that play in. That said, then I have not been disappointed with the pragmatic Dispensable Design of modules yet, whilst over-abstraction using interfaces has burned me more than once. It is not always possible to go with Dispensable Design though. It depends on the situation and making the right choice sometimes requires both thoughtful considerations and experience.

A blog post with examples on both these module design choices is in the works so stay tuned the coming weeks.

Summing up

The intention of layers in Modular Architecture is to support developers in following the principles of component design described by Uncle Bob.

Productivity is increased significantly by having a formalized common solution structure.

Developers in your organization will be able to determine what goes on in a solution that they do not know beforehand quickly when they are able to recognize the dependency flow at once. The architecture and layers makes intent clear.

This means that the time it takes to introduce a developer on a solution that uses the layers of Modular Architecture is minimal when the architecture is followed. He or she will be able to start working on the solution almost instantly instead of having to spend time on getting familiar with unclear dependencies and methodologies.

Changes only affect the features that change and not the entire solution. This lower the amount of technical debt that is added to the solution over time.

In my next post I will show how to use layers in your Sitecore solution and then a post on advanced layering techniques.